Rennie Davis had a gift, no matter what nonsense he spoke, he believed it. This gave him an advantage in flim-flammery which he used to advantage in using people for his own benefit. Whether that was shilling for the Lord of the Universe by which he hoped to obtain the right seat next to God or selling New Age cures and sham ideas in later life. It was his absurd grandiosity and megalomania that inspired and created Millenium '73, a debacle so crushing both emotionally, spiritually and financially that Divine Light Mission and Prem Rawat's career never recovered. This was a good thing, of course, but it was the opposite of what Rennie had in mind. He was such an egotist that he regretted nothing he'd done or said, was ashamed of nothing he'd done or said and probably was saddened by the inability of the world to realise his true greatness.

THE LIVES THEY LIVED

THE LIVES THEY LIVED

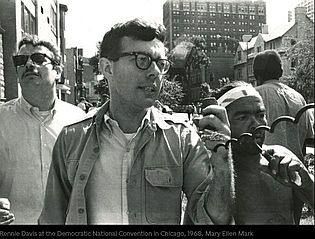

One of the Chicago Seven, he traded activism for enlightenment. By Benoit Denizet-Lewis

On a cool spring night in 1973, more than 1,000 people - students, activists, hippies, spiritual seekers - crammed into a ballroom at the University of California, Berkeley. They had come to hear Rennie Davis, then 32 and one of the most admired antiwar activists in the country, talk about changing the world. Davis was nothing short of a celebrity. Two years earlier, he helped organize the massive May Day protests against the Vietnam War, and in 1969, he and six men, who would come to be known as the Chicago Seven, were charged with conspiracy and inciting a riot outside the Democratic National Convention. Davis was one of only two defendants to testify during the raucous, highly publicized trial, which featured a parade of colorful characters, including an unhinged judge and the defense witnesses Allen Ginsberg and Timothy Leary.

Davis was known for being even-tempered and a relentless organizer, but he combined his seriousness of purpose with charisma and an infectious optimism. While he's portrayed in the 2020 Aaron Sorkin film "The Trial of the Chicago 7" as a nerd who "couldn't sell water to a thirsty man in the desert," as his fellow 1960s activist Frank Joyce put it to me, Davis was actually one of the antiwar movement's most captivating speakers.

Davis would need those skills in Berkeley, where he had come to deliver a stunning message: Activism, he now believed, had failed to fix a broken country. The new solution - to war, poverty, racism - was spiritual enlightenment. "I'm really blissed out with a capital 'B,'" Davis told the crowd. "We are operating under a new leadership, and it is divine. It's literally going to transform this planet into what we've always hoped and dreamed for."

The "new leadership" had an unlikely frontman: a car-obsessed 15-year-old Indian named Guru Maharaj Ji, dubbed the "perfect master." (Writers and activists who struggled to understand his appeal preferred to call him other things, including "the fat kid" and "the paunchy preadolescent mystical magnate.") Maharaj Ji, who now goes by Prem Rawat, was one of countless gurus who gained popularity in the West at the time; the teenager's organization, called Divine Light Mission, had an estimated 50,000 followers along with hundreds of centers and ashrams across the United States. Acting as both devotee and spokesman, Davis insisted Maharaj Ji would bring peace to the world. "God is now on this planet," he announced during a radio interview.

Davis's message was catnip to Maharaj Ji's followers in Berkeley, who danced and placed Easter lilies next to a picture of the boy on a linen-draped altar. But then came the catcalls. "We kept you out of jail, we came to Chicago, and now what are you doing to us?" someone yelled at Davis. "Kiss my lotus ass," another sneered. Activists with "fury bleeding out of every wound," as one writer put it then, hurled tomatoes at their former idol. A homeless man - or prophet, one couldn't be sure - interrupted Davis with cheeky Buddhist riddles.

Things had not gone much smoother at a similar event in New York City. There, Davis tried in vain to convince the crowd that a spiritual focus was "totally consistent with the progressivism and values of political activist work," according to Jay Craven, a young activist and filmmaker who was in attendance. Unlike others in that crowd, he wasn't surprised by what Davis was now selling. Craven had recently returned from visiting Davis in India, where they had sat together on the banks of the Ganges while Davis, looking ethereal in a flowing white cotton tunic, spoke of "the intense white light he experienced when Maharaj Ji put his hands on his forehead and applied pressure to his eyeballs."

Craven left India befuddled, a confusion shared by just about everyone who knew Davis. As the journalist Ted Morgan wrote in this magazine in 1973, summarizing the reaction to Davis's conversion, "Nothing quite like this had happened since Augustine defected from Neoplatonism to Christianity." But there had been signs that Davis was changing, especially after the May Day protests in Washington, D.C. "I never for a minute believed we would literally shut down Washington, but I think Rennie, who was always a grandiose thinker, truly did," Craven told me. Disillusioned, Davis mostly stepped back from the fracturing antiwar movement. Instead, there were acid trips, New Age curiosities and talk of spending a year in the Sierra Mountains.

Davis wasn't alone in abandoning political work for meditation and a belief in effecting social change through inner change. The early and mid-1970s saw "the wholesale transformation of many radicals and activists to new mystical religions," the sociologist Stephen A. Kent writes in his 2001 book "From Slogans to Mantras." The socialist newspaper Workers' Power believed Davis and others had "learned the wrong lesson and decided that politics doesn't work. So, if you can't change the world, change yourself." One of the period's loudest critics of the guru worship exhibited by Davis and others was the writer and biochemist Robert S. de Ropp, who lamented that one could train a dog "and have him presented as the perfect Master, and I honestly believe he'd get a following!"

Maharaj Ji's following was growing by 1973, so much so that Davis hoped he could fill the Houston Astrodome for the guru's appearance and kick-start "the greatest transformation in the history of human civilization." The three-day event was poorly attended and, unsurprisingly, did not bring peace to Earth. When a reporter caught up with Davis in 1977, he had recently moved out of a Divine Light Mission ashram. He was no longer a public figure, he said, because he saw "the process of cleaning up the world as the process of cleaning up your own act first." Davis was now selling insurance, as reflected in the headline: "1960s Activist Rennie Davis Now a 'Straight.'"

But the rest of Davis's life can hardly be described as conventional. After the failure of a company he co-founded to invest in ecologically transformational technologies, he dropped out of society to spend the better part of four years living and meditating at the bottom of the Grand Canyon. Eventually he teamed up with his third wife to teach meditation and build what they called a "new humanity" movement, one "larger than the Renaissance, the American Revolution and the '60s combined."

Still, Davis remained proud of the political activism of his younger years. In 2013, he flew to Vietnam with other antiwar leaders from the '60s to celebrate the 40th anniversary of the Paris Peace Accords. According to Frank Joyce, who was on the trip, some of the long-simmering tensions between activists and Davis resurfaced. "But Rennie was completely comfortable in his own skin and really did have inner peace," Joyce told me. "That can be tough for people to understand. To some leftists, inner peace can be pretty irritating."

Until his death this year from lymphoma, Davis was still predicting an imminent revolution that would transform the world. But as he made clear in "The New Humanity," his breathtakingly optimistic 2017 book, the revolution will need both an inward and outward focus. Though "some activists may want to stay consumed with anger," he wrote, that alone won't save us. "We must heal as a species - starting with ourselves."

Benoit Denizet-Lewis is a contributing writer for the magazine, a National fellow at New America and an associate professor at Emerson College. He is at work on a book about transformation and identity change.